Child's Learning of English Morphology and the Formation of Social Norms

2023

Summary

This paper examines how children learn English morphology and how this process influences social norms and biases. Jean Berko Gleason's Wug Test demonstrates that young children can intuitively apply grammatical rules to novel words, indicating an innate understanding of language. Eve V. Clark's research shows that children gradually refine their word meanings through exposure, while Paul Haward's work highlights how language acquisition reinforces social norms and stereotypes. The study suggests that challenging stereotypes through diverse language models can promote more inclusive thinking and reduce biases ingrained through language learning.

Part 1

The Child's Learning of English Morphology by Jean Berko Review

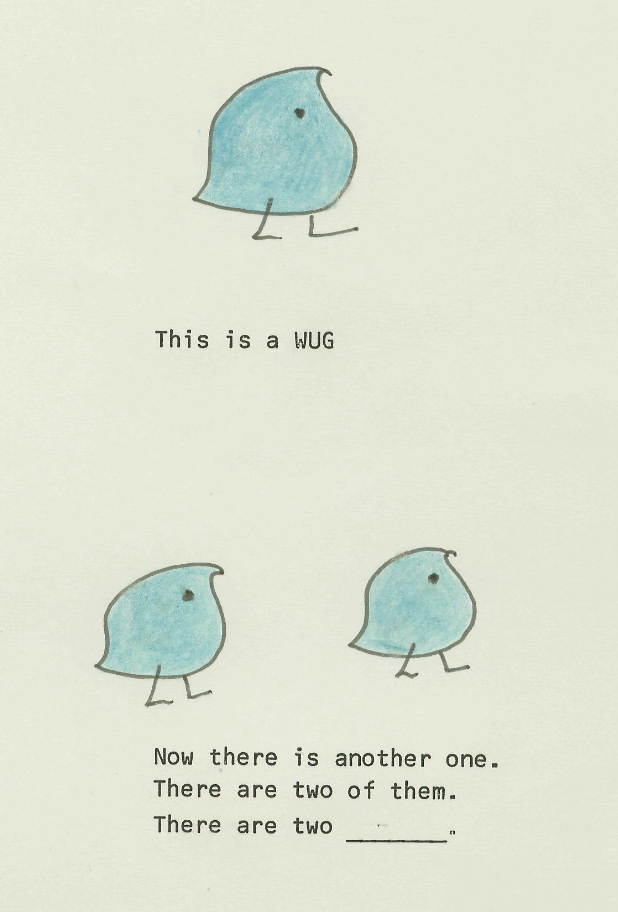

Jean Berko Gleason, a psycholinguist, and professor in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences at Boston University, is known for her essential contributions to understanding language acquisition in children, aphasia, gender variations in language development, and parent-child relationships. During the interview, she gave for PBS News Hour in 2020 for the program Brief But Spectacular, she expressed that "[She] was fascinated by language as a child because [she] was under the impression that whatever you said meant something in some language." Gleason developed the Wug Test to demonstrate that even very young toddlers had an intuitive grasp of language morphology. In this test, a child is given images with gibberish names and then told to form sentences about them.

In her paper "The Child's Learning of English Morphology" (1958), she discusses what children exposed to English morphology learn. The researchers use meaningless materials to evaluate participants' comprehension of morphological rules. It is designed to test the ability of children to learn and use the rules of language to form novel words.

The experiment involves presenting children with a made-up word, "wug," and then showing them a picture of a creature that looks like a bird. The experimenter then asks the child to name the creature, and the child is expected to say "wug." The experimenter then adds a second creature and asks the child to name it, and the child is expected to say "wugs." This simple task is meant to test the child's ability to recognize the word "wug" as a noun, understand that it refers to a specific object, and apply grammar rules to create a plural form of the word.

Linguists and psychologists have widely used the Wug Test to study language development in children. It has been found that children as young as two years old can pass the test, indicating that they have a strong understanding of the rules of language and can use them to create novel words. The results of the Wug Test have also been used to support the theory that children have an innate ability to learn a language and that they are not simply imitating the words and phrases they hear from adults.

Method

According to Paul Alfred Moser's 1950 University of Southern California article "A Rinsland word study of the pupil interest analysis," Dr. Rinsland selected over 100,000 national schoolchildren's compositions from 200,000. He gathered 6,000,000 running words, including 25,000 different ones. He removed words that appeared less than three times at any school level to make a list more realistic. His ultimate list comprises 15,000 words. (Moser, 1950). In the Wug test, the children's correct vocabulary had to be tested to see whether they knew these themes. Given this, Rinsland's list was used to choose the 1,000 terms that first-vocabulary graders use most. Both adults and children were given nonsense word tests, with the results of the adult test serving as the baseline for determining whether or not children's responses were "right." When a child's responses are consistent with those given by an adult, it is said that their answers are "correct."

Materials and Procedure

Following the guidelines for the various possible sound combinations in English, a number of made-up words were created to test whether the child can apply different morphological rules in different phonological contexts. This test aimed to determine whether or not the child was proficient in English. Pictures were then produced on the cards that symbolized the gibberish words. There were 27 image cards, each of which had a picture that was either an item, an animal that seemed like it was taken from a cartoon, or a man engaging in various activities. In addition, multiple new terms have been included for various reasons, which will be elaborated in a later section. Each card had a sentence where a word was left out. The participants were a total of 12, seven of whom were female and five of whom were male; all had at least a bachelor's degree. A significant number of these persons had also completed post-secondary education. Everyone in the room was an English native speaker.

Following the guidelines for the various possible sound combinations in English, a number of made-up words were created to test whether the child can apply different morphological rules in different phonological contexts. This test aimed to determine whether or not the child was proficient in English. Pictures were then produced on the cards that symbolized the gibberish words. There were 27 image cards, each of which had a picture that was either an item, an animal that seemed like it was taken from a cartoon, or a man engaging in various activities. In addition, multiple new terms have been included for various reasons, which will be elaborated in a later section. Each card had a sentence where a word was left out. The participants were a total of 12, seven of whom were female and five of whom were male; all had at least a bachelor's degree. A significant number of these persons had also completed post-secondary education. Everyone in the room was an English native speaker.

Each preschooler was introduced to the experimenter and instructed to look at specific photos. The experimenter read and pointed to the image. The child would provide the missing word, and the word he used was documented phonemically. After seeing all the illustrations, the child was asked why the compound words were chosen that way. "The general form of these questions was "Why do you think a blackboard is called a blackboard?" If the child responded with "Because it's a blackboard," he was asked, "But why do you think it's called that?" (Gleason, 1958, page 153). Different word formations were tested during the experiment; the plural, past tense, derived adjective, third person singular, singular possessive, and plural possessive forms were tested. Example questions for each form are given in the following table.

Results

It was found that the sex difference did not result in a performance difference. However, the performance of the participants changed with age. The first-graders provided more correct, or adult-like, answers than the preschoolers. As a result of young children's ability to supply the appropriate morphological forms for nonsensical words, it may be deduced that children have internalized a set of morphological rules that works in English and can generalize to new circumstances and pick the appropriate form. Table 2 shows the success rate of the kids for each word form.

There were multiple conclusions from the experiment on different forms and patterns. The finding that corresponds to my extended research in the following parts of this paper is the experiment's last portion which tested children's knowledge of complex words' constituent parts. A blackboard is called a blackboard because you write on it, according to most of these kids. A few kids observed the compound words' distinct elements in the older group. They attributed meanings that were not necessarily associated with the word's etymology or the meaning the morphemes may have in later life.

Part 2

In the field of cognitive science, the study of how language is acquired and used has long been a topic of interest. In Part 2, I will gather my research on the papers on children's learning of morphology and the formation of social norms to connect two concepts.

Eve V. Clark's Work

Eve V. Clark, a prominent linguist and cognitive scientist has contributed significantly to developing this gradualist view of learning morphology through her research on language acquisition in children. The ages that children start saying their first words are between twelve and twenty months, according to Eve V. Clark. Grammatical morphemes, such as prefixes, suffixes, prepositions, postpositions, and clitics, are added to words when speakers go from simpler to more complicated ways of expressing their meanings. In her 2017 paper "Morphology In Language Acquisition," Clark states that "Within a particular language, children's mastery of such paradigms may take several years" (Clark, 2017, p.1) caused by several reasons like different levels of meaning distinctions, regularity of the paradigms and language typology. According to Clark, there are four main steps to acquiring noun and verb morphology in kids. These steps are (1) analyzing the structure of words heard in input, (2) identifying terms and affixes, (3) mapping consistent meanings, (4) beginning to use those stems and affixes.

In the second part of her paper, she discusses children's acquisition of inflectional morphology. Some experts believe that children first acquire irregular plural inflections before switching to normal ones. Nevertheless, this seems unjustified because why eliminate a form like feet to express the same object with a different form if children have initially learned its meaning with the first form? Alternately, children typically call periodic structures base stems. They may recognize both breaks and broke as stems or both go and went, without comprehending that both pairings "belong" to one verb. From this perspective, children should add regular inflections to both stems, and they do: they generate both breaked and broked, as if for two separate verbs, and they produce both goed and wented.

Verbs are frequently indicated for person and number and in specific formulations and tenses for gender. Children may learn one or more of the third-person singular present, imperative, and infinitive verbs as their first verbs depending on the language. In English, the first- or second-person present, imperative, and infinitive are uninflected or zero-affix stems, but -s indicate the third-person singular present. Children start with the uninflected form and subsequently indicate the present third-person verb form. Children learn adult alternatives faster when there are fewer affixes to learn to denote plural numbers.

In addition to numbers, gender in nouns and verbs also plays a significant role in children learning plurals. Children learn gender better when the noun and any adjective modifying it have the same prefix. Gender marking in the plural is easier to learn since nouns of the same gender use the same form, and adjectives and verbs use the same affix.

Inflectional systems and word formation appear to depend on at least two factors: the complexity of the meaning being expressed, which children must discover for each affix, and the complexity of the form to be used, which requires children to figure out the conditions that govern different allomorphs. Inflections are first learned as parts of words, then assessed for forms and meanings. To expand paradigms, children can apply affixes to new instances. They also regularize irregular shapes till they can create the right ones.

In her other paper titled “A Gradualist View of Word Meaning,” which was published in 2022, she has shown that young children begin by using words in a very general and imprecise way, and gradually develop a more nuanced and specific understanding of their meanings as they are exposed to a broader range of language experiences. For example, Clark has studied the way in which children learn the meaning of words like "dog" and "cat." She has found that initially, children will use these words to refer to any four-legged animal, regardless of whether it is a dog or a cat. As they continue to encounter and learn about these animals, they begin to use the words more precisely, only applying them to animals that match the specific characteristics of dogs and cats.

As we learn new words and situations, our word meanings can change, allowing us to use language more precisely and complexly. Word meaning acquisition is a lifelong process. Gradualism holds that language experiences shape word meanings. It also emphasizes the importance of a diverse language environment in developing a sophisticated vocabulary and word meanings.

Overall, Eve V. Clark's work on the gradualist view of word meaning has contributed significantly to our understanding of how language is acquired and used. Through her research, she has provided valuable insights into the process by which children and adults come to understand the meanings of words, and has highlighted the role of experience and exposure in this process.

Paul Haward's Work

Paul Haward's 2022 paper "A crucial source of psychological certainty in human cognition: The certainty signature of central form" details how social norms are formed and how learning new words influence social biases. Haward defines social norms as the unspoken rules that govern society's behavior. Socialization and punishment, and rewards for compliance reinforce these norms. Language acquisition shapes social norms. People internalize the meanings and connotations of new words. Language acquisition is crucial to social norms because words shape our understanding of people, places, and things.

According to Haward, "people often form stereotypes for social categories, such as the categories humans use to organize people by gender, ethnicity, and nationality. Sometimes these stereotypes can be somewhat innocuous (e.g., "British people are polite"); at other times, they can be deeply pernicious (e.g., "Black people are aggressive/dangerous)...Upon forming a particular stereotype (e.g., "Asians are good at math"), people seem to represent these traits as "always being present for group members," maintaining these beliefs even when they receive counter evidence over time (a potential reflection of the stability signature of central form). They may also be (over)certain that any given group member they encounter will possess this property (e.g., if they encounter an Asian person, they may initially show a degree of psychological certainty that this person will be good at math)...Finally, if asked why an Asian person is good at math, they may respond with an explanation that simply cites the category ("Because they're Asian!"). These beliefs, which are often quite pernicious, and which unfortunately are all too common, are uncannily similar to the signatures of central form." (Haward, 2022, p.35)

Consider "doctor" and "nurse." These terms refer to healthcare workers with various roles. These words have different connotations. "Doctor" connotes authority, intelligence, and expertise, while "nurse" connotes caregiving, compassion, and nurturing. These connotations can lead to social biases against people in these professions. Language acquisition also reinforces social norms and biases. Consider how certain words describe people of different races or ethnicities. Words can reinforce negative stereotypes and prejudices, perpetuating social biases.

Through language acquisition, individuals internalize the meanings and connotations associated with words, ultimately shaping their understanding of the world around them. This process can reinforce existing social norms and biases and perpetuate societal inequality and discrimination. Haward's papers provide a detailed analysis of how social norms are formed and how learning new words play a crucial role in developing social biases.

Part 3

Children's central form and true generic property can be investigated for social norms and biases. According to Paul Haward, "some things do last forever." The questions I will try to answer in part 3 are: Does the stability signature play a role in forming the stereotypes that remain unchanged over time? How do kids shape form and generic properties through learning new words? Is there a relationship between the children's learning process of English morphology and the formation of their central properties? Can the true generic and form properties be manipulated to change these engraved social ideas? When a child is learning a new word, an accurate word, or a nonsense material, do they unconsciously encode it as a form/general property? Can analyzing how humans perceive a person's central form and generic properties help us understand how people categorize others and form specific ideas and biases?

The concept of "linguistic relativity," which refers to the idea that the language a person speaks can shape the person's perception and understanding of the world, is one of the ways in which the Wug Test demonstrates the influence of social biases on language learning. Another way is through the use of "social biases." This is evident in how children exposed to multiple languages may learn to categorize objects differently based on the words and grammatical structures used to describe them in each language. For instance, a child who speaks English and Spanish may learn to think of a couch as a "sofa" in English and a "cama" in Spanish. This can influence their understanding of the object and their thoughts. Another example would be a child who learns to think of a chair as a "chair" in English and a "chair" in Spanish.

Children learn new words through various methods, including exposure to language, repetition, and context. The process of learning new words plays a significant role in the formation of social biases. As children learn new words, they also learn the associated social and cultural norms, which can include biases and stereotypes. One way that the process of learning new words can create social norms is by reinforcing existing stereotypes. For example, suppose a child is exposed to words and phrases commonly associated with a particular group of people (such as a racial or ethnic group). In that case, they may begin to internalize these stereotypes and view members of that group in a certain way. This can lead to social biases, as the child may begin to believe that the stereotypes associated with a particular group are true. The stability signature, or the tendency for specific information to remain unchanged over time, can contribute to the formation of unchanged stereotypes.

English morphology, or the study of the structure of words, plays a role in how children learn new words and understand their meaning. This process helps the child understand and make sense of the world around them. Therefore, there is a relationship between the children's learning process of English morphology and the formation of their central properties. This understanding is then used to form their central properties or how they categorize and understand objects and people.

Kids shape form and generic properties by learning new words by using them to categorize people and things in their environment. For example, suppose a child learns the word "tall." In that case, they may use it to describe someone taller than the people they usually see. In general, if a child is consistently exposed to words that positively describe a particular group of people, they may develop more positive attitudes towards that group.

The stability signature, which refers to the stability and consistency of a person's characteristics, can form unchanged stereotypes over time. If a person consistently displays certain traits, they may be more likely to be perceived in a certain way and have their stereotypes reinforced. Stereotypes are often based on preconceived notions and biases, and they can persist over time because the people and media reinforce them around us. If a stereotype has a strong stability signature, it may be more likely to remain unchanged over time because it will be more deeply ingrained in our minds. Thus, the stability signature and how children learn and process new words can also form biases.

One example is how language and concepts related to gender roles can create social biases through stability signatures. For example, in many languages, specific words and phrases are used to refer to men and women, such as "he" and "she" in English. These words can create biases by implying inherent differences between men and women and that these differences should be considered in how we interact with and perceive them. Furthermore, the concepts we use to understand gender roles are often based on cultural norms and stereotypes. For instance, the idea that men are "strong" and "assertive" while women are "nurturing" and "emotional" is a common stereotype that is reinforced by the language and concepts that we use to understand gender. This stereotype can create biases by implying that men and women should behave in specific ways based on gender and that deviating from these norms is somehow "abnormal" or "wrong." If a kid learns the meaning of the word "men" by generating a form property of being "strong" because of the stability signature, s/he is going to think that someone who is not "strong" is not a man and would have strong opinions about her/his side of the fact.

The relationship between learning new words and forming social biases is complex and multifaceted. While learning new words can certainly create certain social norms, it is not the only factor involved in forming such biases; whether children unconsciously encode new words as form/general properties is likely to depend on a variety of factors, including the child's age, language proficiency, and exposure to different types of language.

When a child is learning a new word, they unconsciously encode it as a form or general property because the brain constantly organizes and categorizes information to make sense of it. This process is not limited to actual words and can also occur with nonsense materials, as seen in Jean Berko and Paul Haward's work. Thus, there is a relationship between children's learning of English morphology and the formation of their central properties. By learning about the structure and form of language, children may develop specific mental frameworks or schemas that help them understand and categorize the world around them. These schemas can influence their perceptions of other people and their social ideas and biases. Words' true generic and form properties can also be manipulated to change people's ideas and biases. For example, by teaching children words that challenge gender stereotypes or by providing them with a more diverse range of language models, we may be able to help them develop more inclusive and egalitarian ways of thinking. By studying these processes, we can identify ways to reduce or eliminate harmful biases and stereotypes and promote more inclusive and equitable ways of thinking and interacting with others.

Works Cited

Clark, E.V. (2017). Morphology in Language Acquisition. In The Handbook of Morphology (eds A. Spencer and A.M. Zwicky). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405166348.ch19

Haward, P. (n.d.). Some things do last forever: The stability signature of central form. Retrieved December 14, 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/363289162_Some_things_do_last_forever_The_stability_signature_of_central_form

Jean Berko Gleason, Psycholinguist - Brief but Spectacular - PBS

Moser, P. A. (1950). A rinsland word study of the pupil interest analysis (Order No. EP45983). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1563975551). Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/rinsland-word-study-pupil-interest-analysis/docview/1563975551/se-2